“Give me the luxuries of life and I will willingly do without the necessities.” Those were the words of acclaimed architect Frank Lloyd Wright. He was a modernist genius in the most authentic sense. And, he was a man of high ideals and philosophical principles for whom luxury and necessity were inextricable.

Central to Wright’s philosophy of architecture was the conviction that all people are entitled to live beautiful, comfortable lives in beautiful, comfortable places. To that end, he saw architecture was an all-encompassing art form that sought a harmony between the human being, the building, and the natural environment. He even had a name for this: organic architecture.

Architecture with Nature

Wright once stated: “In organic architecture, then, it is quite impossible to consider the building as one thing, its furnishings another and its setting and environment still another.” He saw all these components as parts of a spiritual whole. For that reason, he not only paid close attention to the physical geography he was working in—the details within the homes mattered as well. He was known to personally design features such as furniture, carpets, leaded glass, decorations and dishes.

Prairie School Homes

Frederick C. Robie House in Chicago

However, the landscape was always at the crux of organic architecture. For Wright, there had to be a relationship as well as synergy between the building and its site.

As Wright once stated, “Organic architecture seeks superior sense of use and a finer sense of comfort, expressed in organic simplicity”—a sentiment exemplified by his “Prairie School” homes like the William H. Winslow house in River Forest, Illinois and the Frederick C. Robie House in Chicago.

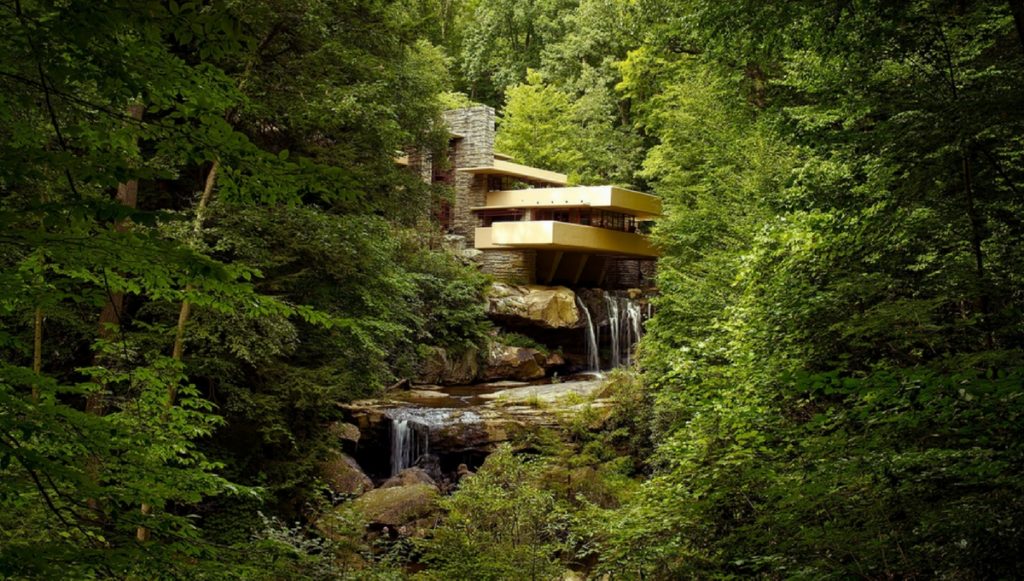

Fallingwater

Fallingwater in Mill Run, Pennsylvania

Wright’s commitment to organic architecture continued throughout his later career. His famous Fallingwater residence—widely regarded as his most beautiful work—was built between 1935 and 1937, and also represents a summation of Wright’s aesthetic and moral beliefs. But his organicism took a more practical turn around this time, when he started producing his Usonian houses.

These revolutionary buildings were developed to suit a range of clients and budgets while conforming to a basic set of criteria. Their windows and eaves were then strategically placed to encourage passive solar heating in wintertime, and shading in summertime. Today, this would be called sustainable design. In this regard, Wright was constantly on the cutting-edge of the architectural techniques and technologies of his time.

Wright’s Lasting Influence

Taliesin West in Scottsdale, AZ

Perhaps this is why Wright’s architecture is so resonant—and relevant—today. Decades before climate change became a hot-button topic, he was endeavoring to devise buildings that—in his words—”belonged” to their surrounding environments. Wherever he worked, he made use of natural, unaltered materials that were locally sourced as well as employed the latest methods to make his structures more efficient and ecologically sustainable. To say Wright’s organic architecture was ahead of its time would be an understatement.

Photos: Chris, David Arpi, Jonathan Lin, david_silverman